In the last two hundred years, laws and customs have changed in most advanced technological societies. This means that the heavy hand of patriarchy cannot prevent you or the people you love from embracing Shakti’s life-affirming energy. It’s Shakti’s energy that brings power and creativity as well as pleasure, love, intimacy and joy into your life – and it’s Shakti’s energy that provides the medium through which you can share these universal qualities with anyone ready to receive them. Unfortunately, the world has not always looked favorably on independent women and men who freely express Shakti’s universal qualities.

We only have to look at the sordid history of witch hunts in Europe and North America in the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. During these three centuries, independent women, midwives and healers were always at risk in patriarchal societies.

However, it’s interesting to note that before 1400 witchcraft was considered a minor offence in most of Europe – and people convicted of witchcraft typically suffered minor penalties such as a day in the stocks.

“But in the 14th century during the bubonic plague (1347–1349) and for decades afterward,” Stephen Katz explains, “people in central Europe focused their fear and rage on witches and plague-spreaders, who they believed were attempting to destroy the Christian kingdoms through magic and idolatry … witchcraft cases increased slowly but steadily from the 14th–15th century … then, around 1550, the persecution skyrocketed.”

Mr. Katz continues by pointing out that “women who seemed most independent from patriarchal norms – especially elderly ones living outside the parameters of the patriarchal family – were most vulnerable to accusations of witchcraft.”

We only have to read this misogynistic excerpt from the ‘Malleus Maleficarum’ to get a sense of the mindset of people living in Europe and North American in the three centuries after the plague.

“What else is woman but a foe to friendship, an inescapable punishment, a necessary evil, a natural temptation, a desirable calamity, a domestic danger, a delectable detriment, an evil nature painted with fair colors?”

The Hammer of Witches

Unless you’re a scholar or an active feminist, you’ve probably never heard of the ‘Malleus Maleficarum’ – and had no idea that a book like this ever existed. Nonetheless, the ‘Malleus Maleficarum’, usually translated as the ‘Hammer of Witches’, had a profound influence on the lives of women, men and children who’ve lived in predominantly Christian countries in the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

The author of this misogynistic masterpiece was Heinrich Kramer a disgruntled Catholic clergyman. His book was published in 1486, thirty years after the invention of the printing press, which is one reason why it was distributed so widely – and why it was able to fan the flames of public hysteria.

Many contemporary authors, including Kramer, took particular aim at women working as herbalists and midwives. Kramer wrote, “No one does more harm to the Catholic faith than midwives. When they don’t kill the children, they take the babies out of the room, as though they are going to do something out of doors, lift them up in the air, and offer them to evil spirits.”

It’s important to note that Kramer wrote the Malleus following his expulsion from Innsbruck, Austria, by the local bishop who cited his obsession with the sexual habits of Helena Scheuberin, a woman he had accused of witchcraft.

Although it was never officially sanctioned or adopted by the Catholic inquisition, Kramer’s book was used extensively by lay courts in Europe during the burning times and afterward in the colonies of North America.

Between 1487 and 1520, twenty editions of the Malleus Maleficarum were published and another sixteen between 1574 and 1669. Along with other misogynistic tracts written during the same era, it contributed to the increasingly brutal prosecution of witches in Europe and North America.

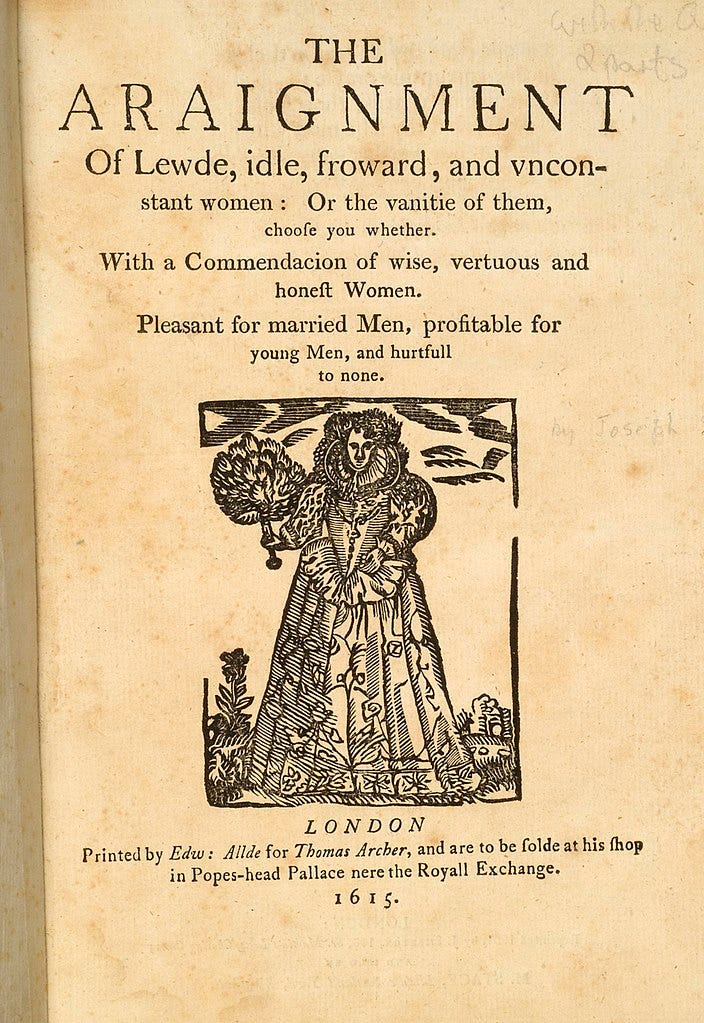

Another author of misogynistic tracts, Joseph Swetnam, published ‘The Araignment of Lewd, Idle, Froward, and Unconstant Women’ in 1615. It depicted women as lustful, wanton, untrustworthy and evil. Swetnam's book went through ten editions between its first publication in 1616 and 1634.

Joseph Swetnam, who wrote in an antique version of English, contended that most “women degenerate from the use they were framed unto, by leading a proud, lasie and idle life, to the great hinderance of their poore Husbands.”

“Women,” he continues, “were made to be the helper of men, but instead they helpeth to spend and consume that which man painefully getteth."

He maintains that women have brought about men’s demise and, like Kramer, he traced men’s dilemma to the fall of Adam and Eve.

In ‘The Araignment of Lewd, Idle, Froward, and Unconstant Women’, Swetnam continues by arguing that a woman’s “beauties are baytes, their lookes are netts, and their wordes charmes, and all to bring men to ruine… Women lay out the foldes of their hare to entangle men into their love, betwixt their breasts is the vale of destruction, & in their beds there is hell, sorrow & repentance.”

Fortunately, the response to Swetnam’s work was swift.

According to Donnalyn Elizabeth of the University of Windsor, “his respondents were infused with an understanding of women's concerns,” and in their retorts, “they present a full spectrum of the debate: a defense of women written by a man and three more defenses written by women.”